With the recent announcement of the upcoming expected closure of the Park City School District Child Care Center and the closing of AristoCats in Kamas last year, many community members are concerned about and confused by this trend. The simple explanation for this nationwide trend is that child-care centers are closing because we do not invest in them as the public good that they are. The private market is failing in early child care because parents are unable to afford high child-care costs, providers operate on razor-thin margins maintaining slim profits, and child-care workers earn low wages and have high turnover.

Given the huge demand for child care in Summit County, why aren’t more centers opening to meet this demand? The answer is that the child-care industry is a market failure because parents can not afford to cover the true costs of child care, and there are not sufficient government resources to address this gap.

Child-care operations are expensive because it is a heavily-regulated industry (as it should be since it involves the safety and care of young children), it is a labor-intensive service, and there is high staff turnover in the industry (26% to 40% of this workforce is estimated to leave their job every year). State licensing rules set the number of adults required for a group of children by age, and the younger the children, the more adults are required to provide care. For high-quality ratings, those ratios are even lower (requiring an adult-to-child ratio of 1:10 for a high-quality rating as opposed to allowing a 1:15 ratio for basic licensing requirements for 4-year-olds, for example).

In fact, 68% of the average cost of caring for an infant in a licensed center comes in the form of salaries and benefits.

The Center for American Progress estimates that the true cost of care for an infant in Utah is $16,600 per year for base-level care, and $27,600 per year for high-quality care. In Summit County monthly tuition for center-based child care range from $935 to $1800 per child, with an average tuition of around $1335. But families can’t afford to pay that much. As a result, in order to try to make the system work, child-care centers struggle to offer competitive wages and operate on razor-thin profit margins that are usually less than 1%.

Let’s look at a specific example. Suppose a fifth-year teacher with a bachelor’s degree teaching in PCSD earns an annual salary of $61,738. and would like to find infant care for her child. She does not qualify for the federal child-care subsidy that is administered by the Utah Department of Workforce Services, because that is available only if she earned less than $49,524.

Infant care requires one adult for every four children and so this teacher’s monthly child-care payment must cover 1/4 of the salary and benefits of the infant care provider as well as a proportional amount of center operational and administrative costs. Luckily, this teacher only has to pay for child care 10 months out of the year, so she finds some savings there. If this teacher is paying $1200 a month for child care, this still represents 19% of her pre-tax income.

In order to lower the parent’s child-care tuition, the center would have to pay the infant care provider less. But the infant care provider can not make any less. According to Utah’s Early Childhood Workforce Index, in 2019, the median hourly wage for child-care workers in Utah was $10.47. Utah early educators with a bachelor’s degree are paid 28.7% less than their colleagues in the K-8 system. In fact, a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education is the college major with the lowest projected lifetime earnings. We have historically undervalued, underpaid, and underappreciated this workforce, which is largely comprised of women and people of color.

“[S]ince the vast majority of the providers are women and disproportionately women of color, the sector benefits from existing unfairness and discrimination in labor markets.”

Child-care workers are leaving the industry because they can earn more income and receive better benefits in less demanding work environments. Nationally, there is an 88,000+ child-care educator shortage. Here in Park City, Vail Resorts is offering $20 an hour minimum wage, which it can do with its over 30% profit margin. The only way to increase the child-care worker’s salary is to charge the parents more. As the PCSD Child Care Center Board member succinctly explained, “the center can’t raise the pay again without pricing out the School District’s teachers.”

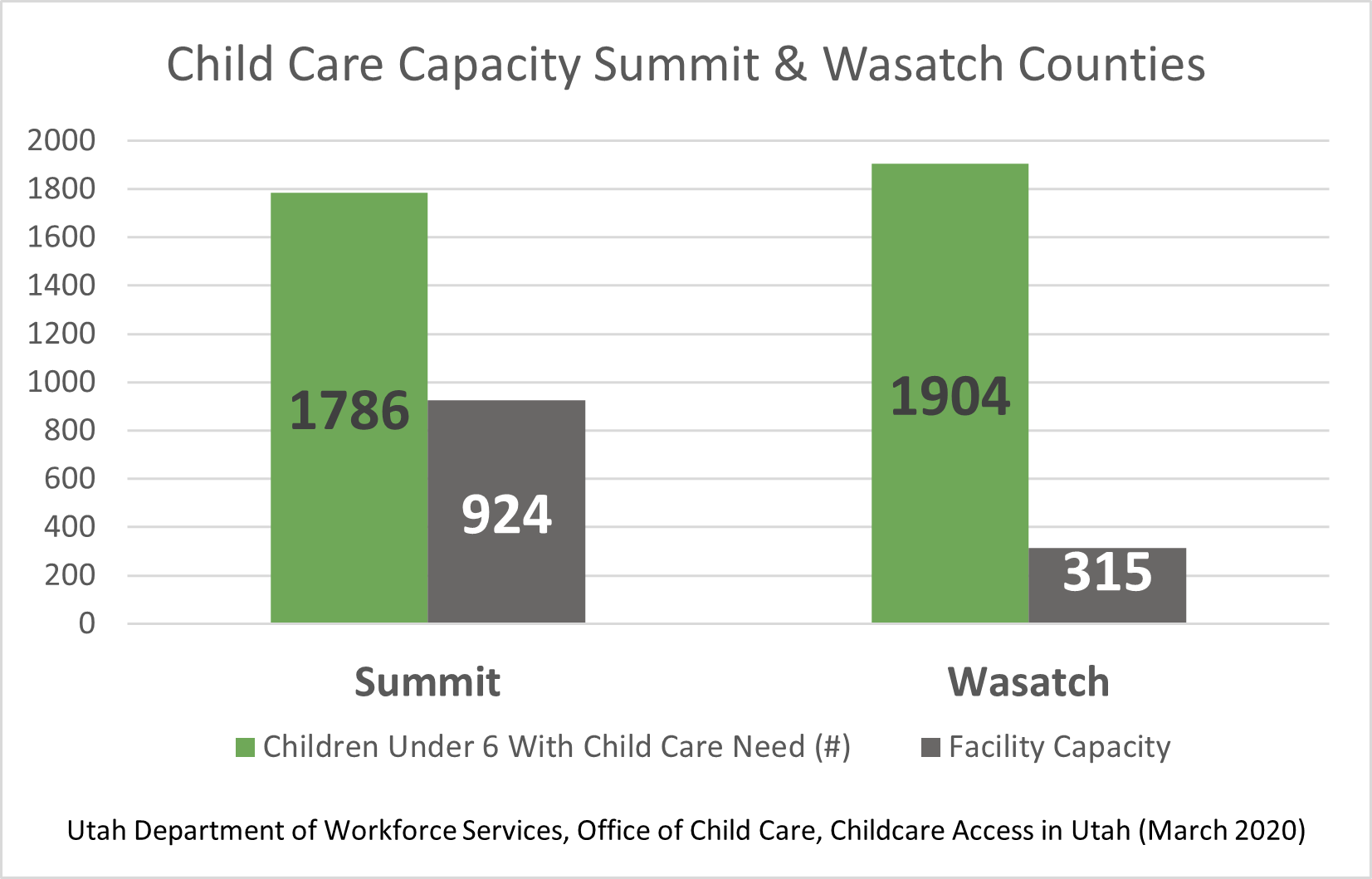

Even before these recent closings, the market failure was evident because there simply were not sufficient child-care options to serve the need in Summit and Wasatch counties. The Child Care Access in Utah analysis finds that Summit County has the third highest rate of children under 6 with a child-care need, and likely overstates our true capacity to meet workforce child-care demand because 319 of the center-based licensed child-care spots in Summit County are located at our local resorts, where these spots are often used by guest children. Moreover, licensing capacity does not account for lower ratios required to offer high-quality care, thus again overstating the actual child-care availability.

To make things worse, the upcoming end of federal relief funds will only exacerbate this issue. Utah’s child-care industry has been supported these past few years by over half a billion dollars ($573,873,964) in federal pandemic relief funds. The Stabilization Grants provide up to $400 per child, per month to licensed centers and have been a lifeline to many providers. Most of these funds have to be expended by September 30, 2023, and the remaining $163 million must be expended by September 30, 2024. Absent major investments by our community, the reality is that more child-care centers are likely to close when the federal funding dries up.

Let’s not let that happen. Instead, let’s acknowledge that Child Care Is A Public Good That Requires Public Dollars.